Animating animators into living characters

In this document, you will find detailed reflections of my process leading up to my workshop. Workshop information can be accessed here, or by following the link provided throughout the document.

Initial proposal

My initial directed studies proposal outline.

Goals

- See whether insights around embodied practices can immerge on the process of visualized storytelling

- See whether animation students feel residual effects, emotional, physical, after experiencing an embodiment workshop.

- Learn the effects of playful exploration of storytelling on individuals

- Students are not focusing on technique, rather, they are asked to pay attention to embodying their environment and characters.

- For my workshop, we are veering away the tacit belief that there is a division between the mind and body.

- To see if participants could infuse their worldview in their storyboards through physical movement and introspection, as well as whether participants had residual feelings from the workshop.

Why explore this workshop

I am interested in how we tell stories, and the effects that a playful physical exploration of story sharing has on a person.

Moving away from the idea of what Eve Bernfield describes as the hierarchy of mind (analysis, concept, idea, etc.) over body (movement, staging, sensory/kinesthetic experience, etc.) in her essay, Exit Descartes: Reimagining Theatre Training Through an Embodied Lens, there is much to be explored around the wholistic relationship between these worlds.

Moreover, the separation of the mind and body has a history of being used as a tool of oppression. The history of the western scientific method and stream of philosophy from a predominantly wealthy, white male patriarchal dominated worldview of control has shaped the narrative to remove ourselves from the capacity to have agency, capacity and trust over our bodies.

In other words, to bring awareness to our bodies is an act of rebellion as much as it is natural.

Embodied storytelling

So, what is embodiment, exactly?

Licensed councillor Melissa Madeson, Ph.D, describes it as rather than accessing it through the head and with words, It’s trusting that those feelings you have inside your body are indicating an experience. It’s also tied to the idea that the mind is integrated in our sensory motor system and experiencing and our cognitive process is led by body-based sensory experiences.

Embodiment practices fall under somatic psychology. Which is described as:

- Events impact our physical, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual being as a whole.

- All events must be processed through our sensory systems.

- Thoughts are physiological and occur throughout the body, not just the mind.

It’s a mix of external sensory perceptions, to internal forces of gravity, to them the interospection of noticing how the feelings inside our own bodies. It;s a body-first approach to brain experiences (embodiment philosophy).

So, why am I exploring this?

Cultivating an awareness of our body’s internal experiences helps to puts the body in the driver’s seat and offers us a sense of aliveness in what we do. It’s about finding ways to live more presently and with intention, rather than sleeping through our lives.

Embodiment practices help us move through our emotions rather than thinking our emotions out of the way.

Think about a time you were angry or frustrated. Your shoulders might have been slumped, you might have felt a tightness in your throat and a burning feeling in your chest. What if you cooled those sensations in your body, before you started to, say, blame yourself for being upset or pep-talk yourself away from thinking about what caused the flare up.

Embodiment practices start by awareness, then towards validating your sensations. You can then decide how you choose to manage those sensations.

The relationship between somatic therapy and storytelling

We know that stories can change the neurochemical processes in our brains. Stories can stimulate our sense of empathy. For example, feel-good stories can release the “moral molecule,” oxytocin. This helps foster more trust and compassion in people, according to professor of Neuroeconomics Studies at Claremont Graduate University Paul J. Zak. His research looks into, amongst other things, the good feelings behind brain connections with stories.

Knowing this, we could take this a step further and explore a story, somatically, within our own bodies. In this way, the story becomes alive within us. It becomes embodied.

Our bodies already process without knowing. Our bodies are memory banks, and recent research has demonstrated that we remember longer in the body, long after our mind has moved on from the event.

When we really connect to other people’s stories, we become a protagonist. We feel what they feel, hear what they hear, smell what they smell. We are moved, we become more alive. The same can be true for our own stories.

Renowned relationship psychologist Esther Perel discusses this sensorial experience of aliveness in her essay on the Eroticism of life. Errotisism is much more than sexual, but it is about what makes us feel alive. It is when we feel the most in tune with ourselves as our senses kick into gear.

Here an exercise on errotisism that Perel’s offers:

I turn myself off when…

I look at my phone before going to bed, sit at my desk for too long, eat candy instead of a meal, think about assignments, etc…

“These are things that zap energy from us,” she writes.

I turn myself on when…

Watching a concert, looking at a sunset, standing under a warm (and cold) shower, after finishing a workout, dancing under multi color lights, singing etc…

“We turn ourselves on when we energize ourselves, when we are embodied, focused,” she writes.

To experience ourselves can be a beautiful thing, and it can be an opportunity to deeply remember our experiences.

Pursuing what excites us as we experience our feelings, and gaining awareness around how our thoughts affect the way we physically (as much as mentally) feel… all this can bring us closer to deeply connecting with ourselves, and with others.

It’s not about saying yes or no to everything; it’s about a willingness to be influenced, receptive, curious.

Esther Perel

So, if we already process without knowing, when we’re shut down from ourselves, what wonders could we discover if we process knowingly? What if that processing happens through living our experiences in a story?

Beginning my research

I began my research looking at the technical aspects of storyboarding. In the past, I’ve taken courses that taught principles of cinematography and storyboarding. However, I’ve sat in on Darren Brererton’s Storyboarding animation class here in ECUAD, and was given ample resources to begin my research.

I also spent time looking at in-person tools used for sharing stories.

Below are my initial keywords

| StoryboardingDigital storyboardingSpatial cognitionOral storytelling | EmbodimentSomatic psychologyExperiential storytelling |

A brief history of storyboarding methods

Disney is credited to have invented storyboarding animation in the 1930’s. Their animator Webb Smith would draw scenes on a piece of paper and pin them individually on a bulletin board.

Today, it’s evolved to the digital format as well, and the formal expands to a variety of methods.

Inspired by the original methods of recording and conveying stories, this video below summarizes the various methods used in storyboarding today.

The process

Professor Darren Brereton of ECUAD’s Faculty of Design + Dynamic media describes the process of storyboarding as:

- Collaborative

- Iterative

- A strong guiding map for cinematography, shooting, movement in a scene, actor cues and elements in a scene.

- Square storyboards are quick, which is necessary for the quick production line

Storyboarding is the Pre-visualization of the film. “Making the film without making the film,” said Brereton.

Animators create a boat board, concept art and initial signs. Once the directors approve the designs, they fill in these ques with animatics (moving boards). After approval, animators will draw the layout, characters and background, and will eventually lead to the polish. That’s where the storyboarding process ends, and production. Animators will break off into focusing on the design (environment, cinematography) and movement (like key animation).

Brereton admits that this process can create silos in studios. Animators working on these separate aspects come together when they’ve finished their work.

[…]

An embodied storytelling workshop conducted in a group, could bring the animation studio together to experience the story together, but bring back their experience to their unique roles.

The pros of drawn storyboarding is:

- it’s iterative

- is quick to produce and at low cost

- there are little limitation of what you can draw within the storyboard

However, this storyboarding process limits animators to use only their heads when depicting a story. A typical production line cuts down on intuitive embodied processes and favours churning out stories. Animators will spend hours hunched over their drawing tablet or table, taking inspiration from nature periodically or from digital content, or drawing from “what they know works,” rather than explore somatically with their bodies.

Brererton and ECUAD animation professor Martin Rose both emphasized how little opportunities there are for animators to physically explore their stories through a facilitated workshop. Animators might explore by filming themselves or observing their environment. That being said, it is not typical for them to take classes exploring senses and movement for the purpose of storyboarding. Many animators are unfamiliar with the concept.

From this initial research, it seems there are very real and potential benefits from slowing down the animation process and having animators experience stories differently.

Other methods + tools for storytelling

I’ve listed below two alternative story exploration methods that have been used for story exploration.

Hand puppets

In the video above, puppeteer extrordinaire Barnaby Dixon demonstrates how to animate animals with his new puppet design.

| ProsEmbodied practiceLosing sense of self | ConsOf these characters are not repeats, it’s not easy making a multitude of them (quick production line issues) |

Three-dimensional computer engines

| Pros: ideal for pre-fabricated stories | Cons: a bit more time consuming |

In the video above, composites are moved around in a 3D environment to help block the scenes and make quick interactions of the story in a preexisting digital environment.

More benefits to storyboarding

We can expand storyboarding to the field of science and social sciences. The storyboarding net are these peer-review articles. A few examples below:

A storyboarding approach to train school mental health providers and paraprofessionals in the delivery of a strengths‐based program for Latinx families affected by maternal depression, by Valdez, Carmen R.; Wagner, Kevin M.; Stumpf, Aaron; Saucedo, Martha. American journal of community psychology, 09/2022, Volume 70, Issue 1-2

Reimagining digital health education: Reflections on the possibilities of the storyboarding method by Lupton, Deborah; Leahy, Deana Health education journal, 10/2019, Volume 78, Issue 6

Using Storyboarding Pedagogy to Promote Learning in a Distance Education Program by Casida, Deborah; VanderMolen, Julia The Journal of nursing education, 05/2018, Volume 57, Issue 5

[…]

In essence, storyboards are wide-ranging, and benefit an array of professionals, both in the arts as much as the physical sciences. This is all the more reason why embodied storytelling can have long lasting and beneficial effects animators and non-animators.

Setting intentions – Indigenous methods of storytelling

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m interested in looking at indigenous principles of storytelling as a way to guide my workshop design. These intentions will help guide the development and shape of my workshop.

I was able to learn more about storytelling principles thanks to my interview with Ronnie Sinclair, a knowledge keeper and pipe carrier from my community.

Attached here are my full interview notes from my call with Ronnie.

Some of my key takeaways from my interview with Ronnie is:

- There are no “folk stories, myths or legends” of the past. Stories aren’t referenced so much in the past, but completely contextual to the moment. They live and breathe. Stories are ongoing conversations with all living things.

- On incorporating myself and participants: Ron incorporates himself in his stories through context and humour. He also gives people a role in the pre- building process for story sharing, being part of the process gives participants permission to share.

- Finding or creating an intentional location to share stories is key for participant engagement.

- Resurgence practice, giving back to community: Part of my practice will have to be a reintroduction to the storybuilding on the land. In recent history, stories have been shared with secrecy and shame, kept in homes and trickled out with ambivalence. The omnipotent presence of the Indian act eroded their relationship with stories, which means eroding their relationship with each other on the land around them.

- Long-term effects of storytelling: Ronnie’s relationship with his environment and living things is much stronger because of the ongoing stories he creates with them. He has a deeper appreciation for all things because he continues to cultivate a relationship through stories.

[…]

Within the context of indigenous storytelling principles, I decided that these would be a few of my intentions for my workshop.

- It’s not about knowing the story by heart, it is about allowing the story to affect you and your soul at a cellular level. It is not about bringing more attention to the brain, but allowing the mind of the body to guide the storytelling design.

– To empower participants into taking the time and space to help them embody their practice

– To treat your expression of the storytelling process not as literal or most proximate to the “best”, but as a true interpretation of your embodied expression.

Background to the story

I’ve chosen to write a story about Wesakechak. This is the Cree name for the Trickster, a well-known character or being in indigenous stories in Canada.

His name is also known to be spelled as Weesagechack, Wisakedjak, Weesaa-geechaak, and named as Nannubush, Naabe, Iktomi, and so on for different nations in Canada. There are innumerable stories about the Trickster, and as Cree author and playwright Thomson Highway puts it, a version of Wesakechak lives across many cultures.

The trickster is known as Nannubush by the Anishinaabe, Naabe by the Blackfoot, and the list goes on. He can change in whatever shape he chooses, he likes to make mischief, adventure, he likes to play tricks on the trees, the animals and even the people. So, Highway recommends that if you ever cross paths with the trickster, it’s wise to offer tobacco.

My story is an amalgamation of a few tales. Descriptions of the Trickster from Thomson Highway’s Laughing with the Trickster, the story of the trickster and the moose from Joyce Clouston’s Journey from Fisher River: A Celebration of the Spirituality of a People through the Life of Stan McKey (whom I’ve had the pleasure to meet), and Cosmologist/science educatior Wilfred Buck, who teaches Lakota, Cree and Anishinaabe stories of the constellations. He shares the story of Wesakchack in the stars.

Thomson highway argues that the English language is too serious to describe how these stories helped us prevail through terror, hunger, starvation, prospect of death, illness, depression. the relationship between us, animals and nature was strong, the lines were blurred, especially at a time when Christianity’s less-humorous God came to our shores (p.96).

The trickster lives in our subconscious, shared psyche. There are many iterations across every single indigenous Nation, and the magick that kept him alive will be the same magick that I’ll use to run my group.

The trickster is here to remind us, as Highway puts it, that if we don’t laugh, we’ll die, that our existence on planet earth is not to suffer or wallow in pain or shame (84). Or, as Ether Perel puts it, to remind us of what makes us feel alive.

The story

Every culture and every person in the northern hemisphere saw the same stars at night, and each person had their own connection to the cosmos. We see Wesakechak the Trickster, up in the sky when the stars align in winter. They can be seen pointing at the seven sisters, known as the Pleiades star cluster, with their hips adorned with the stars of Orion’s belt.

Wesakchak can change in whichever shape they please. One of the first to be blessed on this land by the great spirit, they are a natural adventurer, and like to cause mischief. The trickster likes to involve, to interject, to roar with laughter. And They like to play tricks on people all the time, only to get themself hopelessly entangled in their web of troubles.

Known also as Nannubush, Naabe, Iktomi, and many other names across the land. The trickster is ubiquitous, all existing, and within all of us. The Trickster can even be a Bugs Bunny, a Wile E. Coyote, or a Charlie Chaplin-type, if you think about it. Wesakchak finds their way across all cultures, and they certainly like to visit the animals, trees and people as they’re milling about their business.

Here is one story of Wesakchak told by my friend Stan McKay. One day on the land, the animals got together and had a meeting. They said to each other, we have to do something. The winters are very cold here and our coats are not warm enough. Maybe we should ask Wesakcheak to see if they can help us. Wesakcheak heard nearby. They proclaimed with confidence: “Okay, I’ll make warmer coats for you and I’ll let you know when they’re ready so that you can come and get them.”

One of the things they did was change some of the coats of the animals to winter, for example, the rabbit’s summer coat is brown. So he made a white coat for him to better hide in the snow. The same was true of the fox, who got a shiny undercoat. All these animals got different coats.

The moose however, was on his way to get his winter coat when he began crossing an interesting pond. What he saw under his hooves was a plant in the water that he particularly liked. He had to stop and eat. It was so plentiful. But as the day went by, he didn’t realize how quickly time had passed. He looked up and noticed how dark it was, and cold!

The moose jumped up from his daze and went to Wesakechak to get his coat. Once there, Wesakcheak looked up at him and said: “I’m sorry. There’s only one coat left that is a winter coat. I can’t do any more for you now. I don’t have any more time to work on anything else and that’s the one thing that was meant for you. You’ll have to take it.”

So the Moose got the coat. But it was big, so big, that it just hung loose. That’s why the moose has a coat that hangs loose on his shoulders and especially below the neck. He was late and he didn’t get the right fit.

The workshop – steps

I organized and facilitated an afternoon workshop titled Embodied Storytelling for ECUAD animation students. My aim was to discover whether participants could infuse their worldview in their storyboards through physical movement and introspection, as well as whether participants had residual feelings from the workshop.

My hope was to demonstrate whether embodied story telling practices help visual story makers gain insight in how they chose to share their stories, confidence in exploring new ways to experience their stories, and lose their sense of self to get deeper in their story environment. The workshop was detailed but rewarding, with students participating in a range of playful movement: improv, mindfulness, dance, mask work, and puppetry.

The overall response was positive and demonstrated the success of embodied storytelling as an additional tool for story making. This practice offers possibilities of further developing this workshop for the summer of 2023.

A detailed list of the workshop step-by-steps, including questionnaire feedback, can be read here. Key insights and refections can be read further down this blog post.

Activities

Dancing/movement

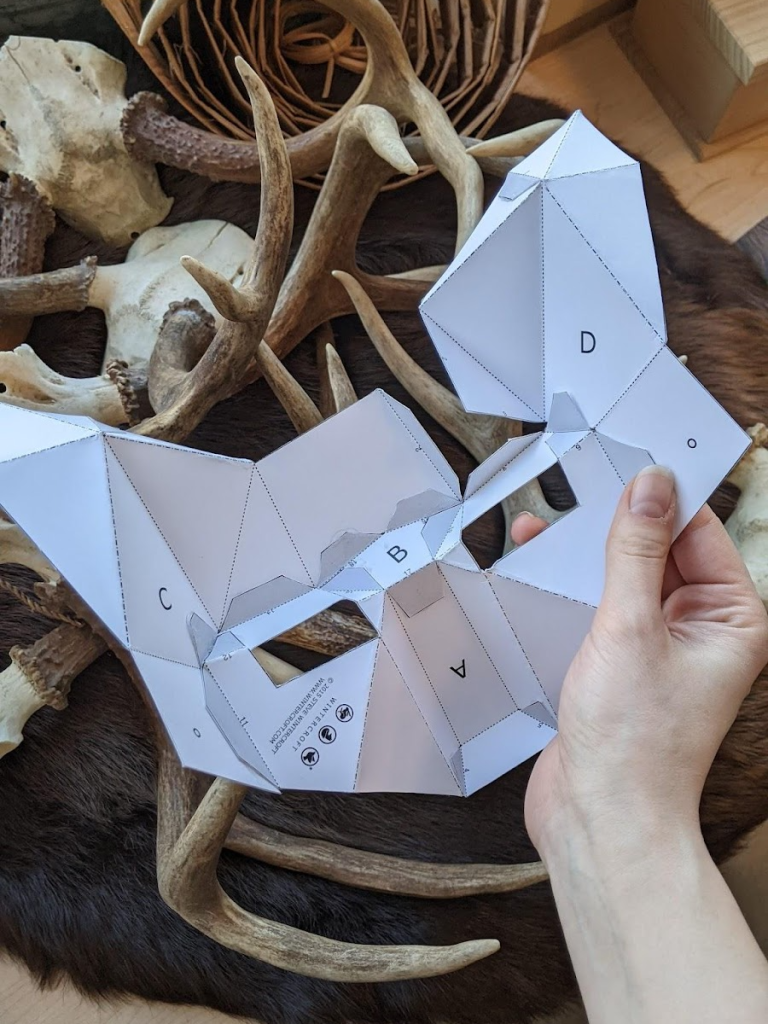

Objects: rabbit mask, moose fox mask, man mask, large monster mask, rabbit ears, comedia de arte masks, mirror.

Participants will choose a mask they like. Now that they’re limbered and energized, they will now explore what these animals are like in the story.

They will look at themselves with it on, move around in it. They will then practice some silly walks with the masks. How would a fox or coyote walk? How would the trickster walk? Or a rabbit, or moose?

I’ll then give them various scenarios for their walk: choose one part of our body that’s holding an orb or weight. Walk as though you have a secret. As if you just discovered a large feast. Walk as if you’ve never seen this forest before. As if you are afraid of those around you. As if you have just lost something precious. Choose another person in the room and try to learn his or her walk. As well, try another mask

I wouldn’t give the participants time to think what “mischievous” “humorous” or “prideful” looks like. We’re just moving as our personas! The only time for thinking is when you’re required to learn something new. Afterwards, I hope that they experience some ensemble group embodiment exercises.

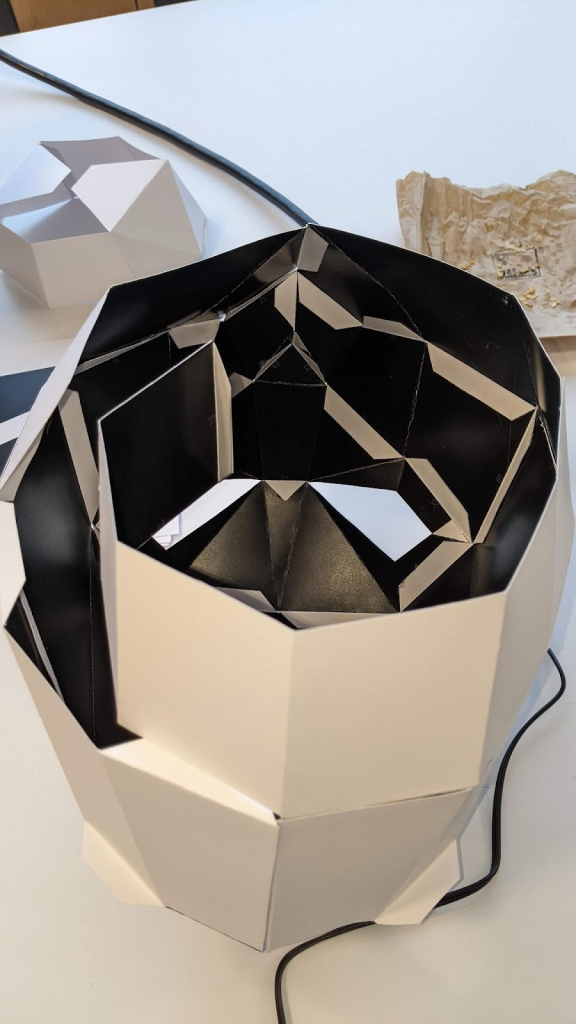

Maskwork

I glued together paper designs from Etsy of a rabbit, fox, moose, and giant man. They took at least 20 hours to make in total for a duration of five to ten minutes of maskwork. However, It was valuable to see how participants would react when moving in the masks.

For information on the step-by-step activities around the maskwork exploration and reflections, please see my workshop information.

Puppetry

The goal of puppetry is to help the group continue embodiment practices through ensemble work, and to feel as the puppet and character might feel like. things that don’t require a complicated learning curve. It’s also important that the puppet designs are ambiguous so as not to steer the storytelling away from their design.

This document helped inform me on the different types of individual puppetry practices we might do, and how to puppet responsibility.

Quote from the reading: “The audience does not fear the puppets and the characters they represent, because they are not real, and thus cannot threaten their security or place in the ‘real’ world. This neutrality allows the puppet to address issues where the normal social and political – 7 – baggage of culture, colour, creed or gender may be a barrier to the message, breaking them down by exaggerating them and dis-empowering their stereotypes. It allows us to examine and perform taboo issues like sex, disease, death, family relationships, gender relations, religion and politics, without offence, or judgement.

Therein lies the tremendous power of the puppet as a tool for education. Because of the puppet’s independence from the human agent, it can convey emotion without causing embarrassment, it can deal with taboo issues without causing shame, it can overcome stigmas linked to discussing sensitive and controversial issues without incurring blame or recriminations.”

How to bring a puppet to life:

Looking at the three principles by Gyre and Gimble’s Masterclass. The breath, the focus and the weight of the puppet. Often we might feel compelled to make big gestures with the puppet, but the secret to bringing it to life is demonstrating those subtleties.

Full photos and videos of the Embodied storytelling workshop can be found here.

Storyboarding

The storyboarding process is inspired by free-form writing. An activity organized during my dance dance, vegitation! workshop in February. I shared the story one last time, and students had seven minutes to draw a storyboard based on what they heard. the process to whitness because they were so intent on drawing their story, a story they got to experience thoroughly over the course of the four-hour workshop.

Questionnaire

Please read the questionnaire answers at the end of this document. I understand that the process of thoughtfully answering questions can zap us out of our embodied practice, so I asked participants to answer the questionnaire the next day. It’s also an opportunity to see the residual aspects of the story and experience that come to surface for the participants.

Workshop: Sticking points

Sticking points are some note-worthy observation I took down during and after conducting my workshop.

- Students were excited about the workshop and appreciated it.

- The interesting, individual elements that people brought from their culture or pop culture was what made their stories unique.

- There were a few speeds of processing: through the body with the activities, and a quieter processing of the

story in their minds. - Students were less comfortable doing movement and mask work exercises but tried regardless.

- The environment played a major role in setting the ambiance for play.

- Music was a great way to get people out of their heads.

- Both helped to bring people out of their shell when ether I or a participant really got into the exercise.

- Adapting the workshop to people’s needs was important.

- Participants tended to use both their experience of the story to old storyboarding habits.

- Participants all knew each other. It might have been different if they were more like strangers.

- I should cue participants to get ready to visualize a story before sharing it.

- Nothing ran long: everyone had stamina to play the warm-up games, and I shortened two of the activities due to participant.

- I felt more unsure about the movement and mask work activities, particularly because I haven’t done them before.

- I was sensitive to people’s hesitation. I am not entirely comfortable leading workshops that have very theatrical roots, because I don’t come from a theatrical background per se.

- I’ve been undervaluing the worth of this workshop by thinking of it as childish and unfounded, and judging it value based on my peers’ interest.

- The process was less enjoyable to make because I did not surround myself with peers who expressed interest in my work.

- The ratio of time that it took to use the masks versus making it was way off. I wish I had found an easier/simpler version of my idea.

- A low-fidelity version of the workshop could have been explored.

- I overlooked the effects of how interaction with other participants could influence their capacity to tell stories.

Key insights

I listed these key insights in my report form, but will reshare them below.

- Curating an environment for playful exploration is as important of a factor to consider as the activities themselves.

- To make the storyboarding process more intuitive, I will better encourage participants to stick with their unique envisioning of the story through the activities and in their storyboards, and encourage loose, broad depictions of their stories.

- It’s important to be aware of and have empathy when leading participants.

- Another low-fidelity version of the workshop could be explored before trying it again.

- There was a symbiotic relationship between the somatic processing of their experience and the introspection of bot the physical and mental processing of their activities. This demonstrates that embodiment storytelling activities require a full body processing, and that may require longer periods of rest or intero- and introspection.

- There is much insight to be gained on silence. Allowing people to process, speak and work in silence were important in this high-energy workshop.

- I need to be proactive to seek help early on, in order to better plan and recruit participants.

- Given my hesitations, I will have to find more research around embodiment and theatre exercises. These aren’t necessarily taught together, strangely enough.

- I would like to explore spatial design/narrative structure using the “playground metaphor.” This means creating an environment that invites the idea of playful behaviour, but in structure in a way that players can participate or abstain themselves, fully engage with other players, and step our and in without much impediment, all while remaining in a playful space.

Conclusion

This process is intended to explore embodied storytelling as a method to convey stories. Embodied storytelling is an exciting and underexplored area of research for visual storytellers and animation studios. A new version of this workshop has the potential to influence beyond animation. It could be useful for people who use theatrical practices to share stories, as well as people, like knowledge keepers, who share stories to deepen their connection with their community.

Bibliography

- AREPP: Theatre for life (2004). INTRODUCTION TO SIMPLE PUPPETRY TECHNIQUES: Participatory Puppet Projects for Classroom and Community Activities. Fourth International Entertainment Education Conference. Retrieved from: https://lhstheatredept.weebly.com/uploads/1/1/9/0/119047293/10.1.1.122.4296.pdf

- Clouston, J. (2021). Journey from Fisher River: A celebration of the Spirituality of a People through the Life of Stan McKay. Second edition. United Church Publishing House.

- Cree mythology written in the stars | CBC Radio. (n.d.). Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://www.cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/from-star-wars-to-stargazing

- Exit Descartes: Reimagining Theatre Training Through an Embodied Lens. (2021, October 18). HowlRound Theatre Commons. https://howlround.com/exit-descartes-reimagining-theatre-training-through-embodied-lens

- Gyre & Gimble Masterclass: Bringing a Puppet to Life—YouTube. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXT3gPef8zo

- Gyre & Gimble Masterclass: How to Make a Puppet. YouTube. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pFEnZfS5IXQ

- Gyre & Gimble Masterclass: Storytelling with Puppets. YouTube. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o85UyC1lZjU

- Highway, T. (2022). Laughing with the Trickster. House of Anansi Press Inc.Intro to Storyboarding. (2016, March 24). RocketJump Film School (YouTube). Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQsvhq28sOI

- Madeson, M. (2021). Embodiment Practices: How to Heal Through Movement. PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/embodiment-philosophy-practices/

- Perel, E. Why Eroticism Should Be Part of your Self-Care Plan. (n.d.). Retrieved April 11, 2023, from https://www.estherperel.com/blog/eroticism-self-care-plan

- Wilcox, H. N. (2009). Embodied Ways of Knowing, Pedagogies, and Social Justice: Inclusive Science and Beyond. NWSA Journal. Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 104-120

- Zak, P. (n.d.) How Stories Change the Brain | Greater Good. Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

Leave a comment